🇯🇵 Japan's boom in randomly-selected mini-publics

Notes from a pioneering frontier of deliberative democracy

Hundreds of deliberative mini-publics and councils have been held in recent years in Japan, in total perhaps the largest number in any one country in the world. Paradoxically, however, the country is little known as being at the forefront of innovation in deliberative democracy.

Our Founder & CEO Claudia Chwalisz was invited to Tokyo in December to address the annual Japan Mini-Public Research Forum. She spoke about DemocracyNext's work on citizens' assemblies, and thanked the Forum members for their Japanese translation of our Assembling an Assembly Guide. In conversation with our International Advisory Council member Hugh Pope, she shares her impressions of Japan's place in the global "deliberative wave".

Hugh Pope: How significant is the upsurge in using randomly selected mini-publics in Japan? What makes Japanese deliberative processes special?

Claudia Chwalisz: Japan staged its first pilot mini-public in 2005. There have now been over 500 deliberative mini-publics (the OECD counts 167 of them as of 2020, and the think tank Koso Nippon has organised another 355). When I was previously leading the OECD’s work on these topics, I was astounded when I first learned about how many examples there are in Japan! My recent trip uncovered even more great work happening across the country.

Most deliberative mini-publics were held in recent years by local governments across Japan, and in some areas they have become anchored into municipal culture. They are usually focused on local planning issues and reviewing municipal programmes to improve them. In comparison with other countries, the municipal performance reviews are an unusually large share of the total.

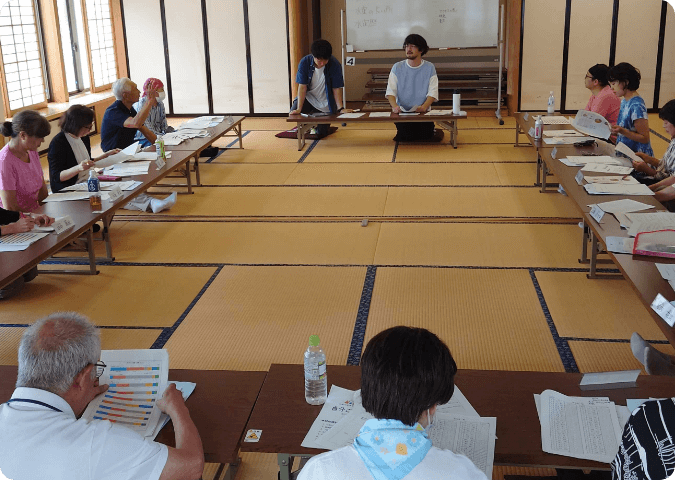

Random selection, deliberation, and boosting public participation are central to all the mini-publics in Japan. These are typically a mix of shimin-togikai (the 1-2 day Japanese version of the German-inspired planning cell) and jumin-kyogikai (typically 4-day residents' councils). More recently, larger citizens' assemblies have begun to be organised. As elsewhere, these are groups of up to 200 people chosen by sortition from a community or country to meet over several days, be briefed by experts, deliberate, and adopt proposals that achieve supermajority acceptance.

Since the beginning, academics have been prime movers for sortition in the country. One is Professor Akinori Shinoto, who spent decades studying civil society in Germany. He was particularly inspired by the planning cell methodology developed by German sociology professor Peter Dienel. Upon returning home, he did much to establish the idea in Japan. Professor Tatsuro Sakano also played an important role in co-founding the Forum. A younger wave of academics have helped to propel this forward in recent years, notably Professors Motoki Nagano, Ayano Takeuchi, and Naoyuki Mikami, among others.

The majority of deliberative processes in Japan are shimin-togikai (a version lasting only one or two days), and have focused on non-controversial topics. This makes them easier to organise and cheaper to run – likely one of the reasons why they have spread so quickly – but it also limits their ability to address complex and controversial issues in depth. Another constraint on addressing national topics perhaps is that cultural norms emphasise respect and conflict avoidance.

The deliberative mini-publics are usually co-organised by the municipal authority and civic associations, notably the Junior Chamber International of young businesspeople. The other example, the residents' councils, are typically more bottom-up, organised by the Koso Nippon (Japan Initiative) public policy think tank. Koso Nippon has convened 335 such councils, involving more than 11,000 people. Koso Nippon is particularly focused on the mini-publics that review local government programmes, and has even experimented with this in Indonesia.

Citizens' assemblies have begun to be held by Japanese cities on the tougher, more universal issue of climate. These are closer to the kinds of assembly we see elsewhere in the world, starting in the cities of Sapporo, Kawasaki, Musashino, and Tokorozawa. These newer assemblies typically last between three to six days.

Is random selection as a new way of decision-making popular in Japan?

Randomly selecting decision makers, or sortition, is not unknown in Japan, and the judiciary has used it for more than a century. There were randomly selected court juries between 1923 and 1943, then 11-person juries acting as a Prosecutorial Review Commission after 1948. Since 2009, in order to make the system more fair for defendants, there's been a system in which six randomly selected lay citizens sit alongside three judges to decide on serious criminal cases.

Japan also used random selection to choose participants for national Deliberative Polls. These looked at a number of issues, including nuclear energy, food safety, and pensions. But Deliberative Polls aim to test public opinion better, not to formulate and propose new policies, as citizens' assemblies do.

Still, randomly selected assemblies are not part of a broader public discussion about democracy or governance in Japan. Whether mini-publics, residents’ councils, city climate assemblies, or Deliberative Polls, they don't get much coverage in the media. Even though they are so widespread, sortition is not widely seen by the wider public as a potential alternative to electing representatives – even among the deliberative democracy community.

Based on my conversations while I was in Japan, people seem generally satisfied about how the country is run. I can see why – when you travel to Japan coming from Europe, in some ways, you think, wow, this country is perfect! But of course, there are underlying issues and concerns, such as the pension system, the cost of living crisis, and a declining birth rate.

A 2024 poll done by Pew Research into 12 high-income countries found that only 31% of Japanese respondents were satisfied with the way their democracy is working. This was one of the worst results in any of the 12 high-income countries surveyed. (A median of just 36% of people across the 12 nations were satisfied with the way their democracy is working, down from 49% in 2021). Turnout in Japan's general elections last year was also among the lowest ever, with only about half of eligible voters casting a ballot.

Do you think mini-publics could offer a way forward on such bigger issues in Japan? Is there any awareness that citizens' assemblies have proved invaluable in solving such tough political-social issues elsewhere, for instance, offering breakthroughs after years of impasse on abortion and same sex marriage in Ireland?

Yes, there is potential for the use of citizens’ assemblies in solving tough political problems. There are several sensitive topics that are not openly discussed in Japanese politics, such as changing the constitution to allow for a female Empress, and how to address the needed changes to the pension system. While there are societal conversations about these issues, they are not typically part of the political debate.

But there is a lack of advocacy for citizens' assemblies at a national level. As far as I know, no prominent figurehead is pushing for a national-level assembly to address controversial or divisive issues, though some at the Japan Deliberative Mini-Public Research Forum were keenly interested in discussing how to mainstream the ideas.

New figures may in time have an impact on the national stage. The President of the Koso Nippon, Kato Hideki, has co-authored a piece advocating for a randomly selected second chamber in Japan. But this idea has not gained widespread public attention.

The community of people interested in the Japanese deliberative democracy movement remains largely academic, concentrated in universities across the country. The challenge is - how to broaden this out?

The academic interest and large number of mini-publics hasn't yet translated into wider public awareness or a significant shift in perspective. As I mentioned, one exception is Junior Chamber International Japan, whose several hundred local organisations grouping business people aged between 20 and 40 have been key partners in supporting the local municipal mini-publics. In general, though, there is a lack of involvement from civil society organisations, journalists, or writers.

How engaged do the Japanese advocates for the mini-publics feel in the global deliberative wave?

It's important to remember that the deliberative democracy movement in Japan was initially inspired and guided by the planning cells developed in Germany and has picked up on the popularity around the world of citizens' assemblies as a response to climate change.

But the Japanese movement appears to be significantly disconnected from broader global developments. Language barriers may be one factor. However, some information is flowing, thanks in part to the Japanese Deliberative Mini-Public Forum’s translation into Japanese of reports from the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and indeed our DemocracyNext guide to Assembling an Assembly.

At the Japan Mini-Public Research Forum conference, I noticed there was a lot of interest in DemocracyNext's work in non-governmental contexts, such as museums, cooperatives, and universities.

The Japanese experience with deliberative democracy is unique and shows how every country has a different way of adapting the global movement for citizens' assemblies. Still, many of the challenges remain the same: shifting from one-off to empowered and institutionalised citizens’ assemblies, deepening awareness of and demand for the advantages of using random selection, and the ever-present challenge of engaging the wider public around these ideas.

What lessons did you take away about the future of citizens' assemblies in Japan?

We have to remember that as in many places, these are still early days. For instance, the Japan Mini-Public Research Forum is only just celebrating its tenth anniversary. The absolute impact may not yet be great, but the acceleration in the numbers is remarkable.

In Kyoto, I also talked with professor Tatsuyoshi Saijo, and he showed how small tweaks in the methodology of deliberation can unleash waves of creativity. Professor Saijo is the pioneer of the participatory model called Future Design, which aims to even up intergenerational justice by taking the long-term view.

One of Professor Saijo's tweaks is a process that asks participants to imagine they are 50 years in the future and looking backwards, and then asking: "How do you get to the future that you want?" That opens up a whole higher level of creativity than situating people in the present asking them to look towards the future. When looking at change from today's standpoint, we can all be very stubborn.

Japan showed me another paradox worthy of wider consideration. In Europe, we sometimes try to over-represent young people in citizens' assemblies. By contrast, Professor Saijo – who doesn't use sortition to choose his participants, but is interested in combining his methodology with citizens’ assemblies – told me that overall, he finds that older people are much more creative about ideas for the future than younger generations.

🙏 I’m grateful to my Japanese hosts for inviting me to Tokyo and Kyoto. Arigato gozeimasu for sharing your insights and learnings from this past decade of deliberative democracy experimentation with me!

📡 What’s on our radar

🎙️Lottocracy is a word we will be hearing more and more, to judge by Alexander Guerrero's excellent podcast interview about his new book about what it means: rule through sortition, or random selection. Previous guests on Paul Zeitz's Revolutionary Optimism podcast are worth your time too: politician-turned-lottocrat Terry Boricius and US champion of citizens' assemblies Nick Coccoma.

📉Few follow public attitudes to governments around the world more closely than Richard Wike of Pew Research. In a new article in the Journal of Democracy, he eloquently lays out how the latest data show "a widespread sense … that representation is broken." Citizens want a bigger role, he says, and new ways to participate. And that, of course, is exactly what we at DemocracyNext and like-minded allies are working on!

☺️ Talking about this new way of doing things, New Yorker writer Nick Romeo answers many questions a sceptic about sortition during an appearance on the Reading Hannah Arendt with Roger Berkowitz podcast. For more on their main topic of discussion, see our lovely video on the Deschutes Civic Assembly on Youth Homelessness.

☮️ Sortition also got a thumbs up for generating ideas for making peace. One of the first scientific papers on randomly selected citizens' assemblies in Bosnia and Herzogovina and conflict-hit areas of the Philippines concluded that peacemakers should consider this as a "radical alternative", and "not only as a supplement to elite-led peace negotiations." As the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue/swisspeace report puts it:

💸We were intrigued too by this rare discussion of how citizens' assemblies can be applied to the choices made by financial institutions like pension funds.

📖 The sortition movement keeps growing! January 2025 celebrated the arrival of the first edition of the Journal of Sortition. Inaugural articles range from a 17th century treatise on using lotteries to critiques of the latest advances in theory and techniques. We wish the best of luck to editor Gil Delannoi, publisher Imprint Academic, and the 31 members of the Editorial Board, whose names from around the world show just how far and how fast this emerging field is developing.

Citizen participation in Japan is different from the West. Coming from Germany and living in Japan, I have been observing this trend for about two decades. It is a model for keeping democracy alive!