Let’s talk about democratising financial institutions

Michael McCarthy joins Claudia Chwalisz to discuss his new book, about democracy’s failures in finance, and how sortition might fix them

This week’s newsletter offers a preview of the kind of content that will be available to paid subscribers in the coming months. Subscribe today to ensure you don’t miss out!

How do we bring the public’s voice, and real decision-making power, into the way that investments are allocated?

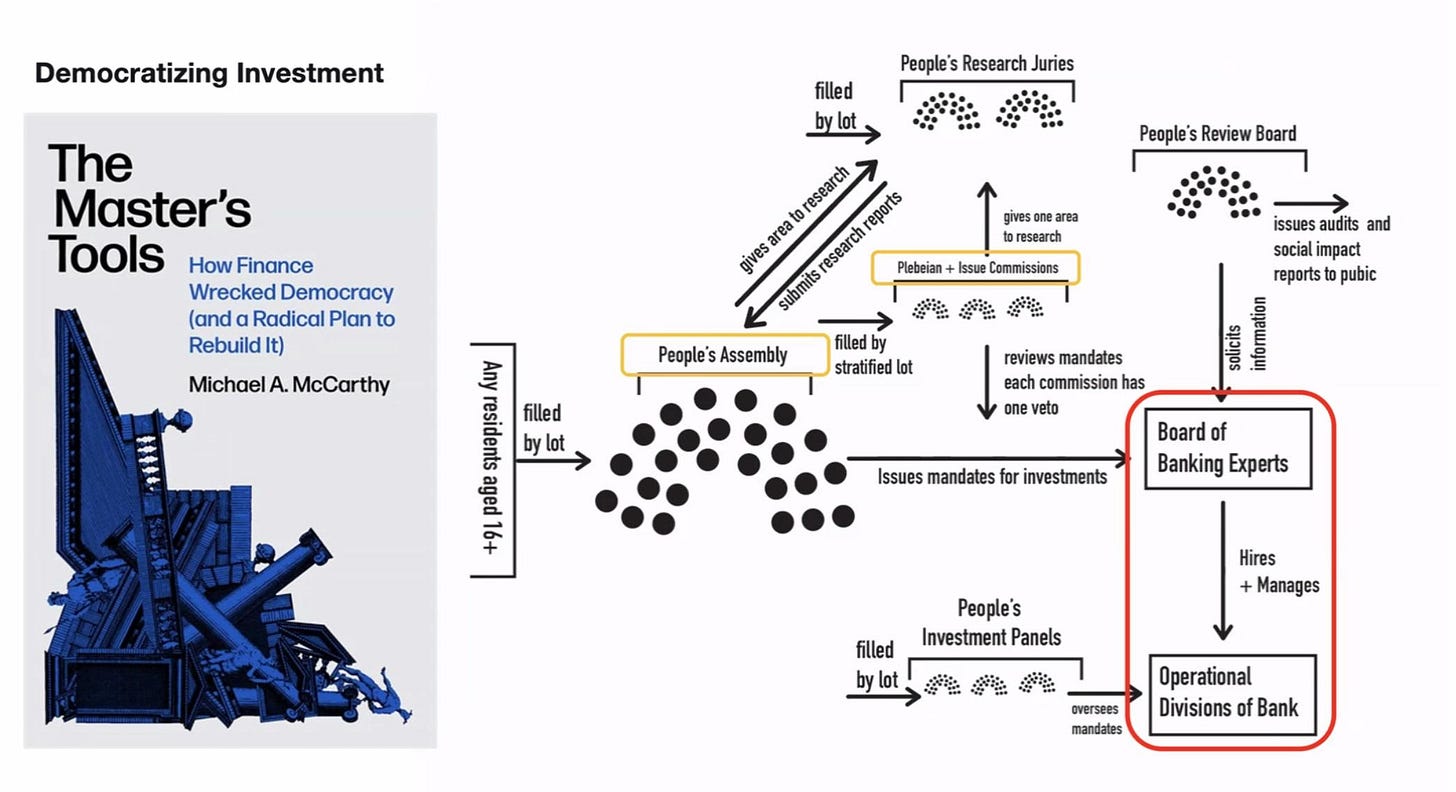

That’s one of the central questions explored by DemNext Economic Institutions Fellow, and award-winning author, Michael McCarthy in his new book, The Master’s Tools: How Finance Wrecked Democracy (And a Radical Plan to Rebuild It), published by Verso Books in January 2025. In this work, McCarthy tackles why democracy is broken today, and offers a bold vision for how it might be repaired.

DemNext CEO Claudia Chwalisz sat down with McCarthy to discuss his background, what led him to this research, and the radical ideas he proposes.

This hour-long interview has been edited for clarity and shortened for the newsletter. You can watch the full conversation here, or listen to the audio below.

Claudia Chwalisz: Why are you interested in these questions about democratising finance, how did this book come about?

Mike McCarthy: Through a lot of research and activism around work that I've been involved in for over a decade now. I wrote a book before this one, Dismantling Solidarity. It’s about the development of the private pension system in the US. The 1930s created a context in which America had the possibility for a really big, robust and universal public system in Social Security. But in the decades that followed that, an increasingly fragmented and employer-based system of retirement was installed instead. That really has been negative for working people in the US.

A big part of that story was how by the 1970s, these pools of finance controlled 25% of all US corporate stock, and were driven by Wall Street investing practices that had negative effects for workers as a whole. And so Dismantling Solidarity describes the loss of control over these investments that working people experienced, principally in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s in the US. There were similar trends in Europe and other places that have private pension systems.

So with my new book, I wanted to ask a more positive and future-oriented question; how some control might be regained. This led me down the path of democracy, sortition, and different forms of democratic governance.

CC: Before your book came out, you wrote an essay on democratising finance. What inspired you to connect ancient democratic practices like sortition to today's financial challenges?

MM: I stumbled into it. I was invited to contribute a paper on democratising finance, which forced me to think about how one would go about doing that technically. What exactly would institutions need to actually bring public voice and decision-making power into investment allocation?

There were two main models out there. One is what we typically think of with democracy; making it public, creating state institutions filled with people chosen by elected representatives. On the other side, you have the Occupy Wall Street model of direct democracy, with these big public forums where anybody could join.

Both paths have major pitfalls. The state institution route is problematic because states are already not democratic. As we know through reams of political science and sociology research, empirical studies, and theory, state institutions already produce oligarchic outcomes. Simply adding more state structures doesn't necessarily make things more democratic, it just expands the problem of the state.

And while the Occupy Wall Street model was exciting and invigorating in many ways, it has profound limitations in scaling up. It might work in very localised situations with few participants, but it becomes impossible to scale while maintaining enough capacity for meaningful participation.

Then there's the issue of self-selection bias. The people showing up are motivated for whatever reason to attend these meetings, which leads to what Jo Freeman called in the 1980s "the tyranny of structurelessness" - leaders emerge who dominate things, but you can't really see that they're doing it.

Sortition [random selection or governance by lottery] was a solution to these two problems. It solved both the problem of elites running things, because random selection, or even stratified sampling based on income, can select out elite overrepresentation. And it got around the problems of self-selection and scaling, because you can do random selection at any scale and get a pretty accurate representation of the population you're trying to draw from.

I didn't have any pre-existing interest in random selection or sortition. But at the time, it was genuinely a solution to a problem I didn't know the answer to.

CC: How would these concepts work in practice for something as complex as finance?

MM: At a basic level, a pool of finance is just assets being invested. Currently, most financial assets are governed by asset managers with a fiduciary duty to maximise returns, which is typically measured against dominant Wall Street trends.

To democratise this, we could build in the perspectives of the actual beneficiaries. Take pension funds - instead of only having trustees make decisions, we could randomly select beneficiaries to deliberate and make decisions about investment mandates.

This deliberation process helps people discover their preferences in ways that voting or surveys don't. When people come together, talk through issues, and weigh trade-offs, they can express what they truly value beyond just financial returns, like social benefits, green spaces, or housing affordability.

CC: Are there real-world examples of this approach?

MM: Yes, the Banco Popular in Costa Rica is governed by randomly selected representatives from different occupational sectors. They make decisions about lending programmes, credit programmes, and services.

Also, in the Netherlands, a large pension fund for retail sector workers recently conducted an experiment where they randomly selected beneficiaries to go through a deliberative process about investments. While this wasn't binding, the participants determined they wanted more green investments and were willing to forego some financial returns for greater social benefits.

CC: You propose "Democracy Fridays" in your book. What do you mean by this, and what would this look like in reality?

MM: I see two versions of democratising finance; a minimalist version involving isolated democratic institutions, and a maximalist vision where most important institutions are governed democratically.

The maximalist vision raises the question: how could this logistically be possible? My answer is that we might need a dedicated day for democratic activity, hence the suggestion of “Democracy Fridays”. It would be a paid workday where citizens participate in democratic governance.

On this day, people would deliberate with others outside their social circles, learn about different value systems, and directly shape society. This would require restructuring our concept of the work week to include public life alongside private work life and leisure.

CC: How do you see the relationship between experts and these democratic assemblies?

MM: In my book, I argue that the experts within financial institutions should act at the behest of democratic mandates. The assembly meets over a period of months, reviews existing mandates, examines alternatives, and makes binding decisions that the experts then implement.

For this to be sustainable, I propose additional bodies, like research juries, that can investigate topics where the main assembly needs more information. These findings would feed back into future assemblies. We should think about what functions different deliberative bodies need to serve, similar to how ancient Athens had many different randomly selected groups for various societal functions.

CC: How has your experience in both academic research and practical policy work shaped your vision?

MM: I've worked with Public Bank LA, which is trying to establish a public bank in Los Angeles, part of a broader California public banking coalition. This led to helping consult on the Public Banking Act submitted to Congress in 2023 by Representatives Rashida Tlaib and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

A key part of that bill specified that banks with over $500 million in assets would need to incorporate some kind of assembly process drawing people by sortition from their region to create mandates for the bank's programmes.

Working in the practical policy world has given me a better sense of what's possible. As theoretical as some of these ideas might sound, I've come to believe they are genuinely achievable in practice.

CC: What about the legitimacy of our current institutions?

MM: We're in a moment where there's a complete loss of legitimacy in both public and private institutions. In the U.S., if you poll Democrats and Republicans on their opinions of different institutions, they're typically on opposite ends of the spectrum. But they converge on their distrust of large corporations, banks, and the state.

This creates an opening - people are searching for alternatives to institutions they see as self-interested, nepotistic, and harmful. So we have a cultural opportunity that might not have been possible a couple of decades ago to introduce more democratic approaches.

CC: How do you see the future of this movement?

MM: I'm encouraged by the momentum I see in certain sectors of politics. Organisations like Democracy Collaborative in the US and Common Wealth in the UK are putting together practical white papers on implementing different forms of democracy in financial institutions.

There's a growing wave of interest in deliberative democracy, and organisations like DemocracyNext are helping to amplify these approaches. Rather than just "catching the wave," these organisations are helping to understand it and infusing it with greater power. Another democratic future is possible when we take the agency to make these ideas happen.

The Master’s Tools: How Finance Wrecked Democracy (And a Radical Plan to Rebuild It) was published by Verso Books in January 2025.

Start a conversation in our chat - who would you like us to interview next?

🔊 On our radar

💲A new initiative, the Courage Calls Us campaign, aims to raise $20 million to support non-profits defending democracy and the rule of law in the United States.

🪸 “The voices of citizens aren't really represented in the multilateral system and trust in climate multilateralism is at an all-time low… We need to reclaim the 'system-disrupting' power of deliberative democracy” - Claire Mellier on Global Citizens' Assemblies.

🚸 Kei Nishiyama's Children, Democracy, and Education argues that children should be recognised as active participants in democratic deliberation, not merely as future citizens to be prepared for adulthood.

🫱🏻🫲🏼 ‘Citizen deliberation in Net Zero governance: learning lessons and looking forward’, explores the role of citizens’ assemblies in the UK as a democratic tool for shaping effective and publicly trusted net-zero climate policies.

🌍 ‘Just sortition, communitarian deliberation: Two proposals for grounded climate assemblies’, highlights five research-backed principles that measurably improve climate advocacy and policy engagement.

🇭🇺 Hungary's first Women's Citizens' Assembly demonstrates deliberative democracy in action, showcasing how 40 randomly selected women successfully developed concrete policy recommendations on gender equality issues.

📑 The NETS4DEM Annual Report provides an overview of democratic innovations across Europe, highlighting successful initiatives and emerging best practices in citizen participation.

🐝 Upcoming events

May 15th, London

Lucy Reid, DemNext’s Chief Strategy & Creative Officer, will be speaking at the Museums and Heritage Show alongside Rob Lewis, Director of Transformation. They will present Citizen power: From the irrelevance of, to pride in, museums, in relation to DemNext’s involvement with Birmingham Museums Trust’s 2024 citizens’ jury.

June 17th, online

DemNext paper launch: Five dimensions of scaling democratic deliberation: With and beyond AI. As interest grows in AI's potential to transform democratic deliberation, the concept of “scaling” has emerged as a key aspiration - but what does scaling democratic deliberation mean and what is the role of AI in enabling it?

Join co-authors Sammy McKinney and Claudia Chwalisz for a discussion moderated by Andrew Sorota, with commentators Oliver Escobar, Kyle Redman, and Manon Revel, for the launch of a new DemNext paper exploring five dimensions of scaling democratic deliberation.

I thought I was the only one who thought we should spend Fridays in civic engagement. 100% support this idea.

Super interesting! In Norway a large coalition of civil society organizations has convened a national citizens assembly on how we should spend our wealth, specifically our Pension Fund. Run and organiser by SoCentral. Read more here: https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/wanted-norwegians-help-form-future-countrys-18-trillion-piggy-bank-2024-10-30/

And here: https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/boards-policy-regulation/how-should-norway-spend-its-cash-solve-global-problems-says-citizen-panel-2025-05-13/