Not a Big Reader? No Problem: How Graphic Artists Facilitate Deliberative Democracy

A new report by Hugh Pope from France

France’s ongoing Citizens’ Assembly on end-of-life issues is proving that reading isn’t always the best way to soak up knowledge or solve problems.

As an observer, I’ve watched as a graphic artists have come to play a critical role in the assembly, where 185 French citizen-members are sorting through complex questions relating palliative care, assisted suicide, euthanasia and related issues.

When taking an important decision – absorbing unfamiliar information, questioning one’s conscience, prioritising options and finding consensus with others – illustrations are proving an excellent assist to the extensive reading materials. It turns out they help with thinking, talking and assembling a final report as well. Perhaps it should come as no surprise: the human brain processes images 60,000 times faster than text, and 90 percent of information transmitted to the brain is visual.

The role of the three artists who accompany each assembly session at first seemed mostly decorative, like the cartoonists who enliven conferences and speeches with real time caricatures of what’s going on.

But by the fifth of nine weekend assembly sessions at the Palais d’Iéna in Paris, it was clear that the artists had taken on a vital interpreting role.

During that session, three artists used two dozen startlingly clear graphic narratives to tell the story of what the assembly had discussed. These mapped out the mental journey participants are on, giving structure, wisdom and even humorous highlights.

Such graphic representation has become a compass for these everyday citizens – almost all newcomers to end-of-life studies – to orient themselves, assimilate concepts and make sense of testimony by experts from the relevant sciences and fields.

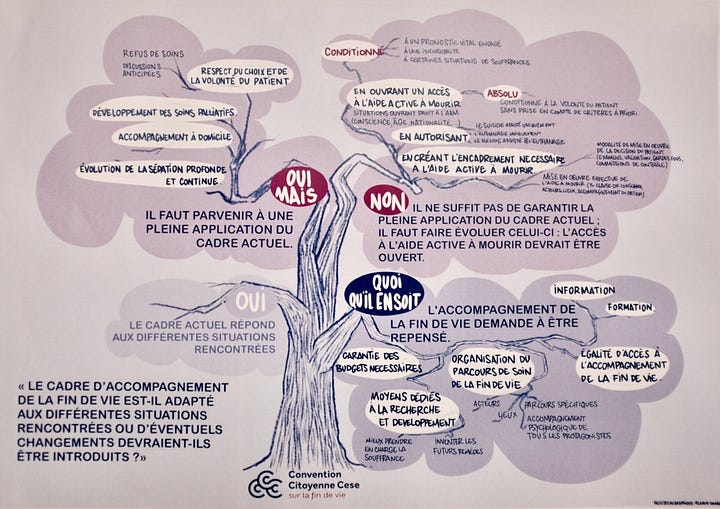

Throughout the deliberation-heavy fifth session, indeed, many people kept open in front of them an artist’s rendering of a “decision tree” that had been printed over two pages in their session's briefing notebook.

"I tore my notebook in half so that I could really see the whole thing while we talk. It helps me see where the discussion is at," one citizen said. "It would be great if we could use graphic art in our final report as well."

The artists’ credibility with the participants is tangible. All sit quietly close to the citizens' deliberations each weekend, listening and rapidly drawing onto tablet computers. “It’s like we’re with the citizens, not judging them,” said artist Chloë Labat, taking a break in the Palais d’Iéna's main collonaded hall overlooking the Eiffel Tower. “We give them easy points of entry into the discussions.”

Over the course of the assembly, the role of the artists has only grown. “We wanted more visibility. So, when we got on stage for the first time, we just kept going beyond our slot," said artist Renaud Combes. "The presentation was really interesting, so we are getting more and more time. The organizers are changing things as we go along, and that’s good.”

Several of the artists said they are self-trained in this new field of graphic facilitation. Combes, a fine arts graduate, said the idea was born in California four decades ago and that he chanced into the field after it spread rapidly in France over the past decade.

Another artist, Stéphane de Mouzon, said he had come to it by way of conference facilitation and the study of mind-mapping. He imagines a fishbone as he turns debates into drawings, teases out a ‘spine’ from the main flow of the talk and then adds ‘bones’ branching off it.

“We are free to put what we like in our drawings,” said Lucie Laustriat, another of the artists. “The main skill is to be able to listen, it’s like being a simultaneous translator. Sometimes we may not understand everything, but we focus a lot on getting the key words right.”

The artists may be independent, but they are open to suggestions. The decision tree, for instance, stemmed from a request by the organizers, who wanted a striking image to help them move forward to developing actionable proposals for the French government to consider.

The timing and design of the decision tree was an “aha” moment for many citizen attendees. Its four main branches clearly mapped the four answers that had emerged from the assembly's deliberations to the main question posed by the government to the assembly: is the current legal framework on accompanying the end of life sufficiently adapted to all situations?

With the graphical decision tree in hand, more people felt empowered to speak. Up to this point, the citizens volunteering to speak had been limited to a self-confident few. Now came clarity, confidence and sometimes eloquence from many sides.

These sprang not just from the aid of graphic art, of course, but from the combination of five weekends of information, expert facilitation and the animators’ use of a fluid, pass-the-baton way of choosing speakers from different self-selected opinion groups.

“It was an amazing change, at times it was a real debate,” said one of the academic researchers following the assembly. “I admit that until now I was wondering, is this [deliberation by randomly selected citizens] all really going to work?”

The artists expressed less doubt about the citizens' potential. “I’m impressed by the level of debate,” Laustriat said. “People really master the subject… And they listen to each other much more than the experts I usually work with. There’s less ego [at a Citizens’ Assembly], things are more horizontal.”

Academic researchers added a question about the impact of the graphic art on the citizens to their studies of the assembly. Another reason for the artists’ success in winning over participants was that they find ways to keep everyone in the same boat.

Stéphane de Mouzon – whose particular genius is comic caricatures with captions that are funny without being hurtful – projected a drawing to the citizens that showed a great bond of humanity that he felt while listening to the groups, even as a minority disagreed on the assembly's emerging tendency to allow some forms of mercy killing.

The artists' inspiration is not a one-way street. “One of you asked us to put leaves onto the Decision Tree, so we’ve now done that as you can see!” Laustriat told the citizen plenary from the stage, winning applause with a tree now robed in green. “You were quite right too. We may be talking about death, but about life as well.”

Some citizens told the artists they feel less intimidated when they see pictures rather than big blocks of text. Combes was touched that when he kept apologizing for typographical errors in his captions from the stage, a citizen came up to him afterward and asked him to stop under-valuing his work.

As the assembly enters its final stages, the graphic artists and citizens may form yet even stronger bonds with one another. “The process of turning deliberation into drawings makes things work out, it makes people agree,” Combes reflected. “As Napoleon said, ‘a good sketch is better than a long speech.’”

Hugh Pope is an advocate for democratic renewal through sortition and is currently preparing for publication on 7 March 2023 his late father Maurice Pope’s book The Keys to Democracy: Sortition as a New Model for Citizen Power. He sits on the Board of Advisers of DemocracyNext. He is a former international correspondent for The Wall Street Journal and author of books on Turkey, the Middle East and Central Asia.

On March 21, Pope will lanuch his late father Maurice Pope’s new book, The Keys to Democracy: Sortition as a New Model for Citizen Power, in a joint event with Professor Yves Sintomer, who is also releasing his own book, entitled The Government of Chance: Sortition and Democracy from Athens to the Present. 👉 Register here.