How to improve on “winner-takes-all” democracy

Democratic norms are changing, and they should resemble friendship more than conflict — read Jane Mansbridge's forward to Felipe Rey's new book

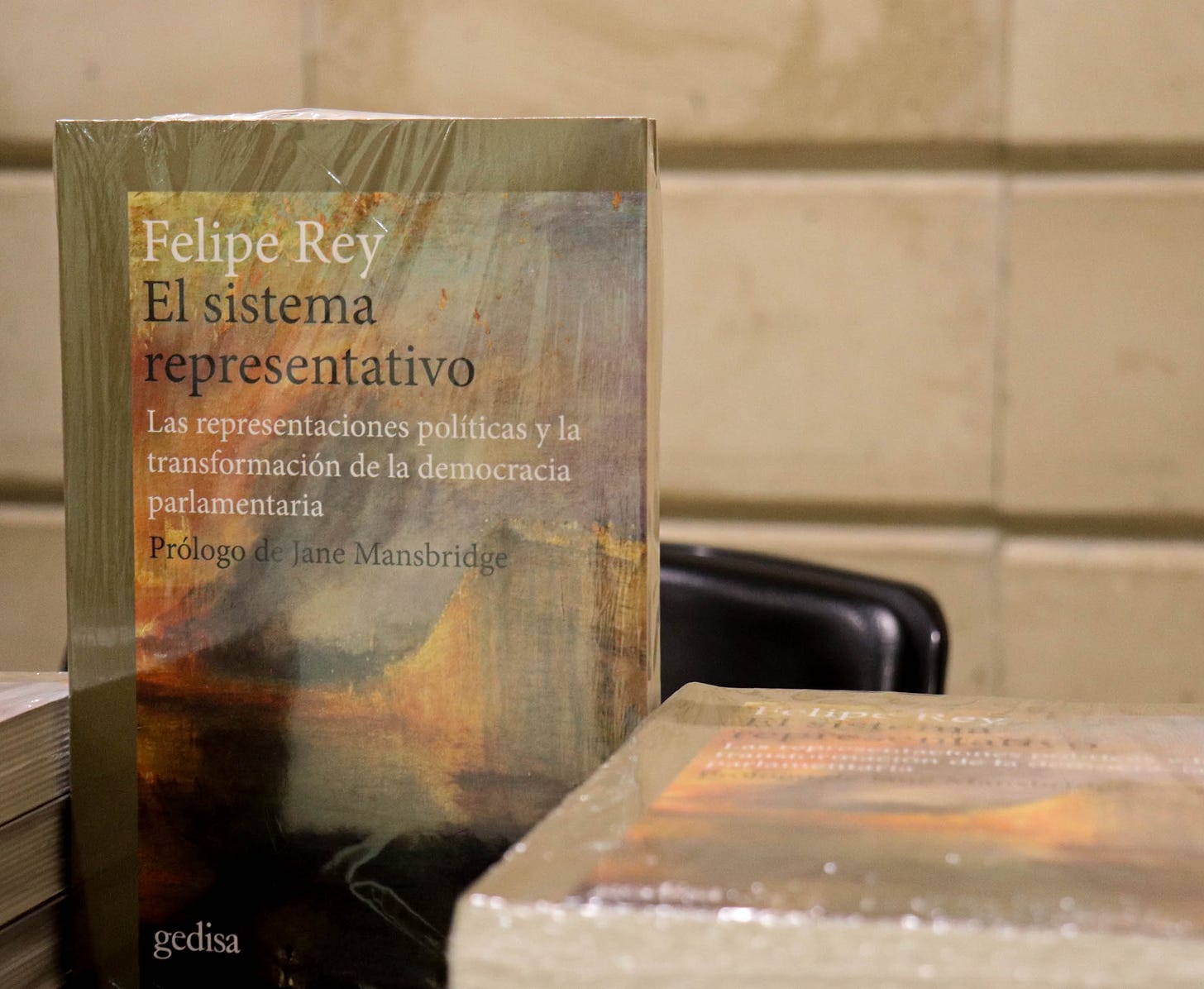

DemocracyNext board member Felipe Rey Salamanca, a public law professor at Pontificia Universidad Javeriana in Bogota Colombia, has just published El sistema representativo — an important new treatise in Spanish which develops the concept of systemic representation beyond elections.

Below, we’re proud to publish an abridged version of Harvard political scientist Jane Mansbridge’s forward to this excellent new book:

Democracy today needs new ideas, and new ideas often arise from the interaction of theory and practice.

Rey beautifully exemplifies this generativity. Much of his work is inductive, grounded in innovative democratic practices. Rey helped design the Itinerant Citizens’ Assembly Model, one of the eight forms of institutionalisation of deliberative democracy in the world recognised by the OECD. He has been importantly behind some of the first experiences with random selection in Latin America.

Political representation has evolved dramatically in the past and will continue to do so. The first representative practices were not electoral. In Athens, more than two millennia ago, members of central public decision-making bodies were selected by lottery and not election. Modern liberal representation is only two centuries old.

Today, some forms of representation are in "crisis," but other forms are emerging. Although two centuries ago the framers of the U.S. constitution conceived of representation explicitly as limiting democracy, in our century the emerging new forms of representation are injecting strands of democratic “self-authorship” more deeply into the representative fibre.

I think Rey is right in arguing that many aspects of our classical democratic theories have become obsolete. As I once put it, this is not your grandmother's democracy. The world has changed and will keep changing. Our representative institutions, two centuries old, cannot continue for two more centuries without creativity and invention.

Citizens’ Assemblies, chosen by lot, are proliferating. Some have evolved from the original form of ad hoc innovations applied to one topic into possibly permanent councils of randomly chosen citizens established by legislatures to advise and perhaps even decide on a wide spectrum of public policies that have come, or might come, before the legislature.

Sometimes by conscious design and sometimes through social evolution, some of these new forms of representation bypass the earlier paradigm of electoral consent. People still want to be represented, but may not be satisfied with the electoral model’s hierarchical and sometimes dysfunctionally contestorial form of representation.

In the coming years, even more egalitarian forms of representation may emerge in the formal and social spaces of the representative system that Rey describes.

Rey makes clear that we now live in a world in which elected legislatures must share their representative space with the significantly developed institutions of the other branches of government and with a dense panoply of societal organisations. In that world, election has lost its monopoly on representation and has given ground to other methods of recruitment such as random selection.

In that world, other entities, such as future generations and animals, deserve representation. In that world, national representation has to compete with global representation both in international organisations and in the global social networks created by new media. This world is dramatically different from the world that, for example, Edmund Burke tried to understand when, in a 1774 speech, he parsed out the distinction between instructed representatives (later called “delegates”) and representatives who followed their “mature judgement” and “enlightened conscience” (later called “trustees”).

How can we know that a system, through its aggregate public policies, represents “the people”? Empirical theorists have an answer: “responsiveness,” which in empirical application means “agreement between legislative voting and citizen opinion”. Rey wants to go beyond this narrow meaning, as do I. For Rey, the norms of good systemic representation should include other criteria, such as inclusion, deliberation, and education.

For a system of representation to be inclusive, salient perspectives and conflicting interests within the population should be descriptively represented, as well as represented in other ways, in the relevant parts of the system. Systemwide descriptive representation helps to communicate varied perspectives accurately, strengthen lines of communication between citizens and representatives, elevate the status of the represented group, and legitimate the eventual decisions. All of these functions serve to include previously marginalised citizens.

As Rey works out the implications of these requirements for good systemic representation, he draws on a distinction I made in the 1980s, in Beyond Adversary Democracy), between “adversary” and “unitary” democracy: a democracy designed for conflict and a democracy that draws from and nurtures both common interests and the qualities of friendship.

Democracy designed for conflict dominates in our current national democratic practice and in democratic thought. Rey concludes that although a system can and should include many kinds of adversarial representatives representing different and often conflicting constituencies, the normative goal of the system is to represent the people as a whole.

In systemic representation, he tells us, the goal is not simply to win. The other party must also win. The system must offer aggregate policies that reflect what the majority wants, but also what minorities need. Normatively, systemic representation should be based on deliberation, negotiation, compromise, and even empathy, not on the "winner-takes-it-all" kind of politics that frequently dominates our democratic practice and thinking.

From that perspective, the norms of systemic representation come closer to friendship than to conflict.

Rey once told me that the idea to write this book, ten years ago, came to him on reading a 2011 article in which I had written that “a full treatment of the larger representative system in politics would take account of …many contested and overlapping formal and informal, legislative and non-legislative relationships.”

Rey took up the baton, and the result is this book, providing exactly that “full treatment” of the systemic approach to representation. His concept of a representative system goes beyond elections to include other forms of non-electoral representation. It goes beyond governmental institutions to include societal actors. It goes beyond the dyadic representation of each representative and the representative’s electorate to ask how the government as a whole can represent the people as a whole. It goes beyond adversary democracy to include the unitary values of friendship and empathy.

At that time, Rey and I did not yet know each other. Now I can imagine other young scholars reading Rey's book and choosing a topic for their own work. Human evolution has fortunately created some institutions, such as universities, that give some people time to reflect on and help refine our ideals. Rey gives us the result in this book. Our practice of democracy badly needs these ideas.

Learn more and purchase El sistema represenativo here.

Obtenga más información y compre El sistema representativo aquí.

🎉 We celebrated International Democracy Day on 15 September, also marking the one-year anniversary of DemocracyNext’s founding! Take a look back at highlights from our launch above. Our founder Claudia Chwalisz also posted a reflection on some of our work so far, including:

the launch of our 78-page Assembling an Assembly (how-to) Guide

the first meetings of our International Task Force on Democratising City Planning

launch of “La Ola Deliberativa,” the Spanish translation of The Deliberative Wave, with INE Mexico

Claudia’s meeting with U.S. President Barack Obama

a recently published paper on the permanent EU Citizens’ Assembly

partnership with Design and Democracy on democratising Museums

our collaboration on Tech-Assisted Assemblies with the MIT Center for Constructive Communication,

a chapter in Mark Miessen’s book on developing new physical spaces for deliberation

ongoing research led by Ieva Česnulaitytė on deliberation as an anti-dote to authoritarianism

👋 Looking for ways to help? Get in touch with us — or share the Assembling an Assembly Guide with your networks using this toolkit!